When thinking about the pioneers of African-American aviation, possibly the most famous are the Tuskegee Airman, the decorated World War II aviators who served their country despite having to fight against racial segregation and discrimination within the US military. Or perhaps you might think of Bessie Coleman, who in 1921 was the first Black woman to earn a pilot’s license and later became a famous barnstorming stunt pilot. Or, more recently, names like Guy Bluford, Ronald McNair, Frederick Gregory, and Mae Jamieson might come to mind, all of them trailblazers who broke racial barriers in space as NASA astronauts. Lesser known, but certainly no less influential, are Cornelius Coffey and Willa Brown, a husband-and-wife pair who were responsible for training many of America’s first Black aviators.

In 1916, a teenage Cornelius Coffey experienced his first flight as a passenger and instantly became fascinated with aviation. In his early 20s, he relocated to Chicago from his home state of Arkansas to pursue a career as an auto mechanic. Memories of that plane ride from many years before never left his mind, though. His success as a mechanic gave him the financial means to pursue flying lessons, but no flight school would accept him as a student due to anti-Black discrimination.

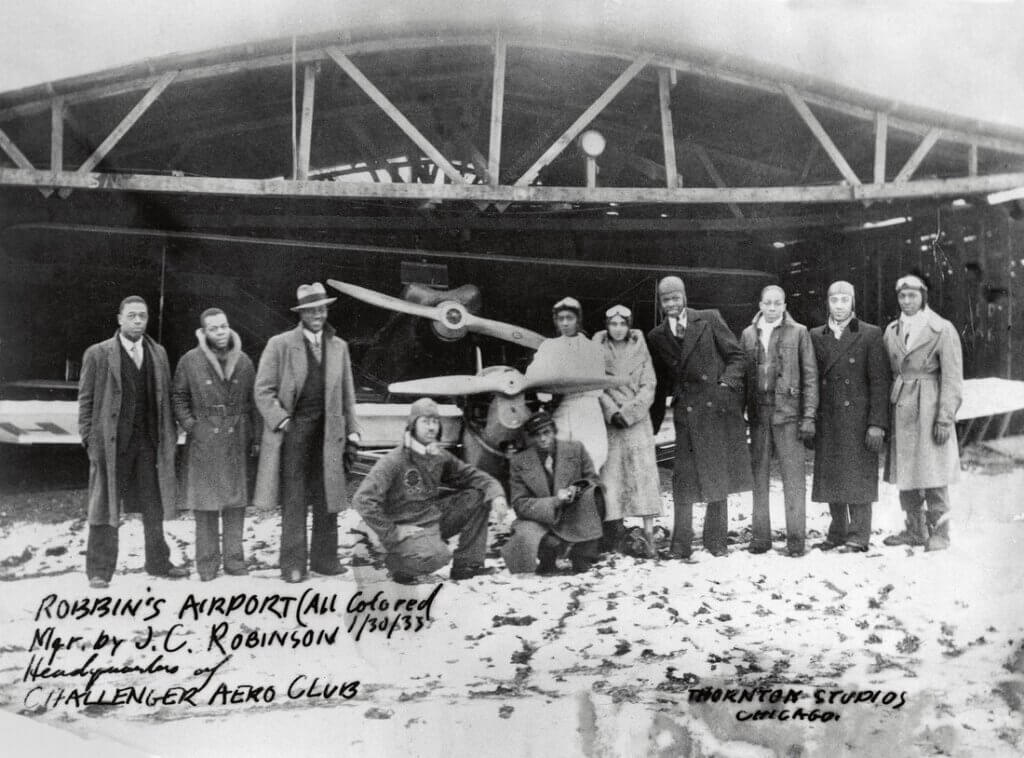

After being denied entry to numerous flying schools, Coffey put his mechanical skills to use. With his friend John Robinson, they built their own single-seat plane that used an old motorcycle engine for a powerplant. They then became self-taught pilots using their homebuilt plane. They knew; however, that they would need official recognition from the proper authorities if they were to continue flying. After attempting to enroll in the Curtiss-Wright School of Aeronautics and once again being denied solely because of their race, they launched a lawsuit against the school for discrimination in 1929. Their suit was successful, and both Coffey and Robinson were accepted into the school’s aviation mechanic program, later graduating as the top two students in their class. Cornelius Coffey became the first African-American to be both a licensed pilot and aircraft mechanic.

Coffey and Robinson then co-founded the Challenger Air Pilots Association to provide flight training opportunities to other African-Americans. He opened a flying school at Harlem Airport near Chicago that was the first in the country to accept students of any race. Among the most celebrated trainees to learn how to fly under Coffey was Willa Brown who enrolled as his student in 1934, eventually becoming the first Black woman to earn a pilot’s license in the United States (Bessie Coleman had to travel to France in 1921 to earn her wings since no flight school in America would accept Black students at that time).

Willa Brown would go on to set many firsts for African-American women in aviation, including becoming the first Black woman to earn a Commercial Pilot’s License (1939). Along with Coffey, she co-founded the National Airmen’s Association (NAA), an advocacy organization whose mission was to increase the number of Black pilots across the country.

In the late 1930s, with the threat of a second World War looming, President Franklin Roosevelt sought $10 million in funding from congress to train civilian pilots who could quickly transition to the US Army Air Corps should America find itself in urgent need of qualified military aviators. Cornelius Coffey, Willa Brown, and the other board members of the National Airmen’s Association feared that Black pilots would be racially excluded from military air service just as they had been during the First World War two decades earlier. Not wanting to be left out again, they devised a publicity stunt: the NAA would sponsor a crew of Black aviators to fly to Washington to personally petition politicians for African-American inclusion in the pilot training program. The NAA selected pilots Chauncey Spencer and Dale White for the job.

In May of 1939, Spencer and White took off from Harlem Airport in a 90-horsepower biplane. After flying over 500 miles to Washington, the pair had a chance encounter while waiting for a DC subway train. Harry Truman, at the time a senator from Missouri, introduced himself to Spencer and White and was captivated by the NAA’s story. Later that day, Senator Truman arranged for a personal tour of their aircraft. Upon seeing the rickety, underpowered biplane, the future president remarked to Spencer and White, “If you guys had the guts to fly this thing to Washington, I’ve got guts enough to see that you get what you’re asking for.”

After the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP) was approved by Congress, among the flying schools selected to receive federal funding were seven run by and for African-American aviators, the most famous being at Tuskegee University. Of those seven, the only one not affiliated with a college was Cornelius Coffey’s flying school at Harlem Airport in Illinois, which he renamed the Coffey School of Aeronautics.

When the United States entered WWII in 1941, Willa Brown attempted to join the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs), but she was rejected due to her race. She would instead find other ways to serve her country during the war. Now married to Coffey, the pair ran his flying school together, with Cornelius responsible for flight instruction and aircraft maintenance and Willa serving as the school’s administrator and ground school instructor. Together, they trained over 200 future Tuskegee Airmen. Brown also joined 613 Squadron of the Civil Air Patrol (CAP) and became the first African-American CAP officer. During the war, her unit flew US-based anti-submarine and border patrol flights, freeing up other military pilots for service on the front lines in Europe and the Pacific.

Unfortunately, Brown and Coffey’s marriage would not last. The pair divorced in 1948, the same year President Truman ordered an end to racial segregation in the US military in large part due to the wartime success of the Tuskegee Airmen. Both Cornelius and Willa continued to have careers in aviation. Willa Brown taught aeronautics and served on the FAA’s Women’s Advisory Committee, the first Black woman to do so. Cornelius Coffey continued to fly until he was 89 years old, just two years before his death in 1994. Today, IFR pilots flying along the Victor airway into Chicago Midway International Airport (KMDW) use a waypoint known as the “Coffey Fix” (COFEY) named by the FAA to honor Cornelius Coffey’s contributions to American aviation.